2.8 Sussex Multi-agency Procedures to Support Adults who Self-neglect

Contents

- 2.8.1 Introduction(Jump to)

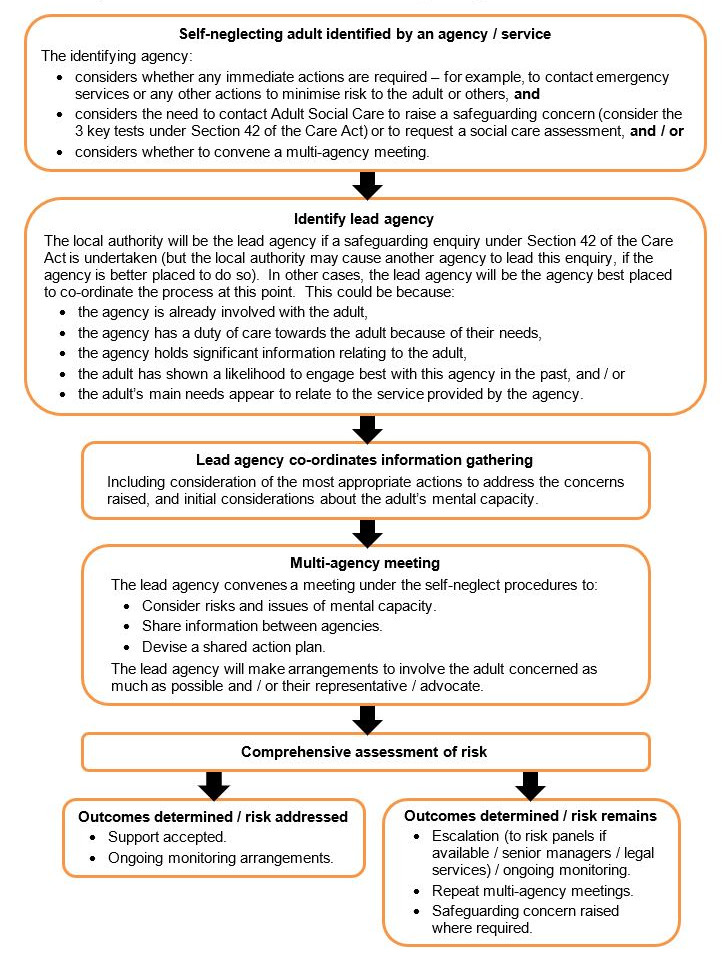

- 2.8.2 Flowchart - Overview of the self-neglect process in Sussex(Jump to)

- 2.8.3 Self-neglect and the Care Act 2014(Jump to)

- 2.8.4 Self-neglect: signs and causes(Jump to)

- 2.8.5 Working with adults who self-neglect(Jump to)

- 2.8.6 Self-neglect and mental capacity(Jump to)

- 2.8.7 Collaborative multi-agency working(Jump to)

- 2.8.8 Comprehensive assessment of neglect (including risk assessment)(Jump to)

- 2.8.9 Multi-agency review meeting(Jump to)

- 2.8.10 Legal remedies and other options(Jump to)

- 2.8.11 Self-neglect: checklist for practitioners(Jump to)

Self-neglect covers a wide range of situations and behaviours. It can be linked to numerous factors including:

- physical health problems,

- mental health problems,

- substance misuse,

- psychological and social factors,

- diminished social networks,

- personality traits,

- traumatic histories and life-changing events.

A failure to engage with adults who are not looking after themselves (whether they have mental capacity or not) may have serious implications for, and a profoundly detrimental effect on, an adult’s health and wellbeing. It can also impact on the adult’s family and local community.

Analysis of Safeguarding Adults Reviews in relation to cases involving self-neglect has set out the following learning and recommendations:

- The importance of early information sharing in relation to previous or on-going concerns.

- The importance of thorough and robust risk assessment and planning.

- The importance of face-to-face reviews.

- The need for a clear interface with safeguarding adults procedures.

- The importance of effective collaboration between agencies.

- Increased understanding of the legislative options available to intervene to safeguard a person who is self-neglecting.

- The importance of an understanding of, and the application of, the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

- The need for practitioners and managers to challenge and reflect upon cases through the supervision process and training.

- The need for robust guidance to assist practitioners in working in this complex area.

- The need for assessment processes to identify carers and / or significant others, and the level of care and support they are providing.

Aim of these procedures

These procedures set out a framework for collaborative multi-agency working within Sussex to provide a clear pathway for all agencies to follow when working with adults who are self-neglecting.

The aim of these procedures is to prevent death and serious harm to self-neglecting adults by ensuring:

- Adults who are self-neglecting are empowered, as far as possible, to understand the implications of their self-neglecting behaviours.

- A shared, multi-agency understanding and recognition of the issues involved in working with adults who self-neglect.

- Effective multi-agency working and practice, whether this falls within a Section 42 safeguarding enquiry or outside of this. Decisions will be made on a case-by-case basis as to whether the lead agency will be the local authority or another agency. Please refer to the flowchart in section 2.8.2.

- Agencies and organisations uphold their duties of care.

Who the procedures apply to

These procedures are to assist professionals from any agency who are working with and supporting an adult who is displaying self-neglecting behaviours.

Any professional can request and convene a multi-agency meeting under these procedures. Where a safeguarding enquiry is being undertaken, the local authority will be the lead agency under these procedures. In other cases, discussions will be held by the agencies involved as to who is best placed to co-ordinate and convene a multi-agency meeting and response. See section 2.8.7 of this guidance for further information on multi-agency meetings.

Flowchart - Overview of self-neglect process in Sussex

See section 2.3 of the Sussex Safeguarding Adults Policy and Procedures for more information on Section 42 enquiries.

The Care Act 2014 formally recognises self-neglect as a category of abuse and places a duty of co-operation on all agencies to work together to establish systems and processes for working with adults who are self-neglecting. The Care Act emphasises the importance of early intervention and preventative actions to minimise risk and harm. Central to the Care Act is the wellbeing principle, and focusing on decisions which are person-led and outcomes focused. These principles are important considerations when responding to self-neglect cases.

Under Section 42 of the Care Act, a safeguarding enquiry is required when the person who is self-neglecting meets the three key tests – that is, the person:

- has needs for care and support (whether or not the local authority is meeting any of those needs), and

- is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect, and

- as a result of their care and support needs is unable to protect themselves from either the risk of, or the experience of, abuse or neglect.

The Care and Support Statutory Guidance states that ‘self-neglect may not prompt a Section 42 enquiry. An assessment should be made on a case by case basis. A decision on whether a response is required under safeguarding will depend on the adult’s ability to protect themselves by controlling their own behaviour. There may come a point when they are no longer able to do this, without external support’.

Section 42 enquiries are primarily aimed at adults who are experiencing abuse, harm, neglect or exploitation caused by a third party.

In addition to the statutory duty to carry out a safeguarding enquiry under Section 42 of the Care Act, local authorities have a power to undertake a non-statutory safeguarding enquiry if it is proportionate to do so and will promote the adult’s well-being and support a preventative agenda.

Decisions are made on a case-by-case basis. Situations which present with a lower level of risk, which could include adults who are not in receipt of health and social care services, and have not been known to Adult Social Care previously, could potentially be addressed through mechanisms such as:

- engaging the adult in a Care Act assessment,

- signposting to alternative services or community resources,

- arranging for mental health services and support, or

- contact with GP etc.

Professional judgement and risk assessment is key in determining the level of intervention required. Any factor or issue may move a lower risk case into a higher threshold which would warrant consideration under safeguarding procedures and / or consideration of other legal remedies. Where there are indicators that the level of risk is likely to change, appropriate action should be taken or planned.

Indicators of significant risk could include:

- History of crisis incidents with life-threatening consequences.

- High risk to others (consider risks relating to substance misuse, or risk of fire associated with hoarding).

- High level of multi-agency referrals received.

- Risk of domestic violence.

- Fluctuating capacity.

- History of safeguarding concerns or the person being vulnerable to exploitation.

- Financial hardship, including risk to tenancy or home security risks.

- Likely fire risks.

- Public order issues, including antisocial behaviour, hate crime, offences linked to petty crime.

- Unpredictable or chronic health conditions due to non-compliance with the proposed treatment.

- History of chaotic lifestyle, including significant substance misuse or self-harm.

- Environment presents high risks, such as inadequate plumbing, washing or toileting facilities.

- History of non-engagement.

- Little or no informal support network, socially isolated.

In all cases, when a concern is raised regarding self-neglect, all agencies have a responsibility to consider these procedures for supporting adults who are self-neglecting. This is regardless of whether the concern falls within the scope of a Section 42 enquiry or not

It should also be remembered that children can be affected by adults who self-neglect. Where there are concerns for a child in the context of an adult experiencing self-neglect, Children’s Services should be contacted – whether or not the concerns relate to child protection or a child being ‘in need’. If child protection procedures apply refer to the Sussex Child Protection and Safeguarding Procedures.

Self-neglect is “the inability (intentional or non-intentional) to maintain a socially and culturally accepted standard of self-care with the potential for serious consequences to the health and well-being of the adult and potentially to their community” (Gibbons, 2006).

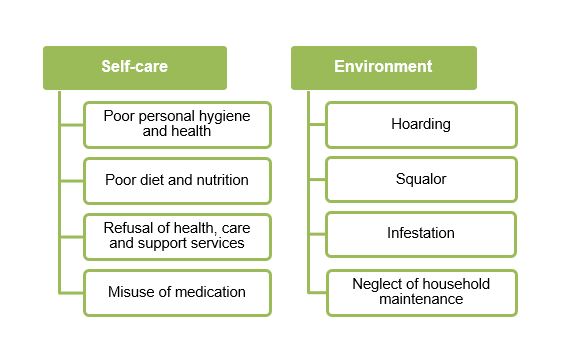

Self-neglect can describe a wide range of different situations or behaviours. It might mean that someone is not looking after their own health or personal care. In other situations, it might refer to someone not maintaining their home environment for so long that it becomes cluttered or dirty enough to pose risks for their health or safety.

Indicators of self-neglect

- Living in very unclean, sometimes verminous circumstances.

- Neglecting household maintenance creating fire risks or hazards, eg. rotten floorboards, lack of boiler, dangerous electrics.

- Displaying eccentric behaviours or lifestyles, such as obsessive hoarding.

- Poor personal hygiene and poor health, eg. unkempt appearance, long finger nails and toe nails, pressure sores, malnutrition and dehydration.

- Poor diet and nutrition, eg. little or no fresh food, or mouldy out-of-date food, and there is evidence of significant weight loss.

- Declining prescribed medication or necessary help from health and / or social care services.

- Collecting a large number of animals who are kept in inappropriate conditions.

- Financial debt issues which may lead to rent arrears and the possibility of eviction.

- Excessively cluttered environment which poses a fire risk and access difficulties.

This list is not definitive or exhaustive.

Reasons for self-neglecting behaviour

Self-neglect may happen because the person is unable to care for themselves or for their home, or because they are unwilling to do so, or sometimes both. They may have mental capacity to take decisions about their care, or may not.

There are a range of explanations and contributing factors which may lead to self-neglect, including:

- Changes in physical or mental health, including age-related changes.

- Influence of the past, such as bereavement and loss, a traumatic event or childhood trauma.

- Chronic mental health difficulties which may include: personality disorder, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder.

- Alcohol or drug dependency or misuse.

- Diminishing social networks and / or economic resources leading to social isolation.

- Fear, anxiety, pride in self-sufficiency.

Often the reasons for self-neglect are complex and varied, and it is important that health and social care practitioners pay attention to mental, physical, social and environment factors that may be affecting the situation (Braye, Orr, Preston-Shoot, 2015).

Unpaid carers may self-neglect as a result of their caring responsibilities. Workers should be aware of the impact that caring for a vulnerable person might have on the carer, and ensure that a carer’s assessment is carried out and appropriate support offered.

Self-neglect and hoarding

Hoarding can be described as the excessive collection and retention of goods or objects. Hoarding disorder is a persistent difficulty in discarding or parting with possessions because of a perceived need to save them. Hoarding can often become a concern for others when health and safety is threatened by the nature or amount of items accumulating within, and sometimes overflowing from, the property of the person who is hoarding.

The reasons why someone begins hoarding are not fully understood. It can be a symptom of another condition. For example, someone with mobility problems may be physically unable to clear the huge amounts of items accrued. Compulsive hoarding can cause significant distress or impairment of work, family or social life.

Until recently, hoarding was considered to be a symptom of conditions such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), anxiety disorder or autism. However, as a result of significant research, it is now recognised as a distinct mental health disorder, and is included in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), 2013. It is therefore crucial that the correct support and guidance is sought when working with adult’s who are hoarding, such as arranging a medical review or referral to mental health services.

Home safety visits

Where a person’s home environment becomes cluttered through the excessive hoarding of items, the risk of a fire occurring increases, and it is more difficult for adult’s living within the property to evacuate safely.

With the consent of the adult, the Fire and Rescue Service will undertake a home safety visit and provide the necessary guidance and advice regarding fire safety, and also where necessary will install smoke alarms and / or other specialist equipment. Any partner agency can make a referral for a home safety visit by contacting the Fire and Rescue Service in their area. The adult, or a friend or family member, may also make a self-referral.

The starting point should be the adoption of a person-centred approach and engaging with the adult who is self-neglecting. This will support their right to be treated with respect and dignity, and to be in control of and, as far as possible, to lead an independent life.

Key principles of engagement

When engaging with an adult who is self-neglecting, and who may have difficulty with their executive functioning (the ability to plan, organise and complete tasks), consider whether:

- They have information in a format they can understand.

- Circumstances allow conversations to take place over a period of time and the building-up of a relationship.

- Consider who (e.g. family, advocate, other professional) can support you to engage with the adult.

- Always involve attorneys, receivers, or representatives, if the adult has one.

- Check whether the person understands their options and the consequences of their choices (consider the person’s mental capacity).

- For adults who present with fluctuating capacity, aim to develop a plan of agreed actions or outcomes for the adult during a time when they have capacity for that decision.

- Ensure the adult is invited to attend meetings, where possible.

The challenge of non-engagement

A frequent challenge encountered by professionals when working with adults who are experiencing self-neglect is when adults refuse, or are unable, to engage with or accept services to support them and to minimise risk. There will often be competing demands between demonstrating respect for the adult’s autonomy and self-determination, and the need to protect the adult from harm.

Non-engagement can present in a variety of ways, including:

- Not attending appointments.

- Not opening the door to professionals.

- Being unable to agree to a plan of support to effect change and minimise risk.

- Being unable to implement recommendations to reduce risk.

- Being too substance affected to engage in any support.

Self-neglect needs to be understood in the context of each adult’s life experience; there is not one overarching explanatory model for why adults self-neglect or hoard. It is a complex interplay between physical, mental, social, personal and environmental factors. It is likely that self-neglect is the result of some incident or trauma experienced by the adult, for example childhood trauma, bereavement or abuse. This may also lead to a person becoming demotivated and developing a poor self-image and self-esteem, which will impact on their ability to engage with professional support. Positive outcomes can be achieved through approaches informed by an understanding of the unique experience of each person. It is imperative that all multi-agency practitioners remain non-judgemental, and have a shared and compassionate approach to understanding the complexity of the adult’s history and background and how this has led to their current circumstances.

Where an adult refuses support to address their self-neglect, it is important to consider mental capacity and ensure the adult understands the implications, and that this is documented. A case will not be closed solely on the grounds of an adult refusing to accept a support plan.

Organisations involved in supporting an adult who is self-neglecting may have a non-engagement policy. All professionals must refer to their own policies in addition to these procedures.

Effective interventions

In multi-agency partnership settings, it is important to consider who may be best placed to work creatively and proactively with an adult who does not wish to engage, and who can build a relationship of trust that may enable the person to accept support. For example, the adult may have already established a positive working relationship with another professional, such as a worker from a voluntary agency, or care agency or health service. In these situations, these workers have a crucial role in leading interventions which may help the adult to accept support, and in co-ordinating input from other agencies with specialist expertise. It is important that organisations have mechanisms in place for supporting these workers to undertake this role, and to escalate any concerns where necessary.

Staff who are supporting those presenting with self-neglect need to receive supervision of their work according to local policies. Group or team reflection of self-neglect cases and consideration of relevant research is also encouraged. In order to deliver high quality supervision, all supervisors and their managers should have an up-to-date working knowledge of these self-neglect procedures. This will ensure that managers and leaders are well equipped to deliver appropriate supervision, guidance and support to frontline staff. All staff should attend specialist self-neglect training where this is relevant to their role.

Finding the right approach to working with an adult who is experiencing self-neglect and seeking to understand the meaning and significance of the self-neglect for that adult is also critical in achieving the best outcomes. For example, adults who have lived during the war may see that everything has a value, or some who have inherited possessions from deceased relatives may find they cannot ‘sort’ these out due to a sense of loss. An over-directive approach is unlikely to support the development of a positive working relationship, since self-neglecting adults may have been living with shame and fear about their circumstances and as such may be sensitive to what presents as a criticising manner. Similarly, it is important to use appropriate language. Adults may prefer the term ‘collecting’ rather than ‘hoarding’, and the word ‘rubbish’ has a tendency to demean the items which may be important to the person.

“At the heart of self-neglect practice is a complex balance of knowing, being and doing” (Braye, Orr and Preston-Shoot, 2014):

- Knowing, in the sense of understanding the person, their history and the significance of their self-neglect, along with all the knowledge resources that underpin professional practice.

- Being, in the sense of showing personal and professional qualities of respect, empathy, honesty, reliability, care, being present, staying alongside and keeping company.

- Doing, in the sense of balancing hands-on and hands-off approaches, seeking the tiny opportunity for agreement, doing things that will make a small difference while negotiating for bigger things, and deciding with others when the risks are so great that some intervention must take place.

The table below is based on work by Braye, Orr and Preston-Shoot (SCIE, 2014), and illustrates various methods and interventions to support effective practice in working with adult’s who are self-neglecting.

|

Theme |

Examples |

|

Building rapport and being there |

Taking the time to get to know the person, treating the person with respect, refusing to be shocked, maintaining contact and reliability, monitoring risk or capacity, spotting motivation for change. |

|

Moving from rapport to relationship |

Avoiding kneejerk responses to self-neglect. Talking through the person’s interests, history and stories. |

|

Finding the right tone and straight talking |

Being honest about potential consequences while also being non-judgemental, and separating the person from the behaviour. |

|

Going at the adult’s pace |

Moving slowly and not forcing things; continued involvement over time; showing flexibility and responsiveness. Small beginnings to build trust. |

|

Agreeing a plan |

Making clear what is going to happen, for example, a weekly visit might be the initial plan. Offering choices and having respect for the person’s judgement. |

|

Cleaning or clearing |

Being proportionate to risk and seeking agreement to actions at each stage. |

|

Finding something that motivates the adult |

Linking to interests, for example, hoarding for environmental reasons or linking to recycling initiatives.

|

|

Starting with practicalities |

Providing small practical help at the outset may help build trust, for example, household equipment, repairs, benefits, ‘life management’. |

|

Bartering |

Linking practical help to another element of agreement – bargaining. |

|

Focusing on what can be agreed |

Finding something to be the basis of the initial agreement that can be built on later. |

|

Risk limitation |

Communicating about risks and options with honesty and openness. Encouraging safe drinking strategies or agreement to fire safety measures or repairs. |

|

Health concerns |

Facilitating or co-ordinating doctors’ appointments or hospital admissions. Providing practical support to attend appointments. |

|

External levellers / enforced action |

Ensuring that options for intervention are rooted in sound understanding of legal powers and duties. Setting boundaries on risk to self and others. Recognising and working with the possibility of enforced action. |

|

Networks |

Engaging with the person’s family, community or social connections. |

|

Change of environment |

Considering options for short-term respite if required, for example, to have a ‘new start’. |

|

Therapeutic input |

Replacing what is relinquished, for example, through psychotherapy or mental health services. |

Balancing adults' rights and agencies' duties and responsibilities

All adults have the right to take risks and to live their life as they choose. These rights will be respected and weighed when considering duties and responsibilities towards them. They will not be overridden other than when it is clear that the consequences would be seriously detrimental to their or another person’s health and well-being, and where it is lawful to do so. Adults should be informed of their rights and the agency’s duty of care. Staff will also consider the person’s right to privacy and information sharing under the General Data Protection Regulations weighed against the level of risk to the person and others who may be affected. Agencies should consult their Caldicott Guardian if concerned about information sharing.

In situations where an adult refuses to engage and their self-neglect places them at significant risk, professionals may need to meet and make plans without the adult present. This is only done as a last resort when risks are significantly high and cannot be mitigated through partnership working with the adult and multi-agency colleagues.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) is crucial in determining what action may or may not be taken in self-neglect cases.

The MCA is designed to protect those who cannot make decisions for themselves, and is underpinned by human rights principles which aim to ensure its provisions are applied in a way that respects our human rights.

When assessing the mental capacity of an adult who is self-neglecting, it is good practice to consider carrying out joint capacity assessments, for example, involving an occupational therapist who can assist with assessing the adult’s functional ability and executive capacity (see section on decisional and executive capacity).

Assessing mental capacity

An adult should be presumed to have capacity. However, there may be cases where an adult may lack understanding and insight into the impact of their self-neglecting behaviour on their or others’ wellbeing. When an adult’s behaviour or circumstances cast doubt as to whether they have capacity to make a decision, then a mental capacity assessment should be carried out.

Robust mental capacity assessments are critical in determining the approach to be taken by professionals, either to support the decision-making of an adult with capacity or to intervene to protect the best interests of an adult who lacks capacity. Any mental capacity assessment in relation to self-neglect must be time-specific and relate to a specific intervention or action. The assessment should be appropriately recorded.

It is important to clearly document how a worker has maximised an adult’s autonomy and involvement within the capacity assessment, ensuring they have been given all practical support to help them reach a decision for themselves. In relation to self-neglect, this will include exploration of the adult’s understanding of their behaviours and associated risks, including:

- Can they report back to you what the risks are?

- Can they report back to you that they know their behaviour places them at risk?

- Can they report back to you the consequences of taking these risks?

- If the risk is death, explore what the adult’s understanding and beliefs are regarding their death.

Good practice is to record the actual questions as they were asked, and the responses provided by the adult.

Adults who self-neglect may be reluctant, or find it difficult, to engage in the assessment of capacity. Please refer to section 2.8.5 ‘Working with adults who self-neglect’ for further guidance on engagement.

Fluctuating capacity

Some adults may have fluctuating capacity. This is particularly common in situations of self-neglect. It may occur as a result of their lifestyle or behaviour, and lead to making an unwise decision, for example:

- An adult may decline treatment for an overdose when under the influence of alcohol.

- An adult may prioritise a substance over a serious health need.

- An adult experiencing very high levels of distress and making unwise decisions such as those with emotionally unstable personality disorder.

This fluctuation can take place over days or weeks, or over the course of a day. Consideration should be given to undertaking the mental capacity assessment at a time when the adult is at their highest level of functioning.

Other adults may have a temporary impairment of their ability to make decisions due to an acute infection. The key question in these situations is whether the decision can wait until the adult has received treatment for the infection. In emergency situations, it is necessary to proceed with the best interests decision making process.

For adults who have ongoing fluctuating capacity, the approach taken will depend on the ‘cycle’ of the fluctuation in terms of its length and severity. It may be necessary to review the capacity assessments over a period of time.

In complex cases, legal advice should be sought.

Decisional and excutive capacity

SCIE report 46 ‘Self-neglect and adult safeguarding: findings from research’ highlights the difference between capacity to make a decision (decisional capacity) and capacity to actually carry out the decision (executive capacity).

Good practice includes considering whether the adult has the capacity to act on a decision they have made (executive capacity).

Where decisional capacity is not accompanied by the ability to carry out the decision, overall capacity is impaired and interventions by professionals to reduce risk and safeguard wellbeing may be legitimate.

Frontal lobe damage is an example of a condition which may cause loss of executive brain function, resulting in difficulties with understanding, retaining, using and weighing information, and therefore affects problem solving and the ability to act on a decision at the appropriate point.

Unwise decisions

Principle 3 of the MCA enshrines a person’s right to their own values, beliefs, preferences and attitudes. However, this right does not absolve an agency from their duty of care, and anyone supporting an adult who is self-neglecting must ensure they have met their professional responsibility.

Where an adult has capacity and may be making what others consider to be an ‘unwise decision’ does not mean that no further action regarding the self-neglect is required, particularly where the risk of harm is deemed to be serious or critical.

The duty of care extends to gathering all the necessary information to inform a comprehensive risk assessment. It may be determined that there are no legal powers to intervene. However, it will be demonstrated that the risks and possible actions have been fully considered on a multi-agency basis.

It is also important for those supporting an adult with self-neglecting behaviours to have insight into their own values and beliefs in order to avoid any bias against what could be perceived as unwise decisions and behaviours.

Inherent jurisdiction

Taking a case to the High Court for a decision regarding interventions can be considered in extreme cases of self-neglect, ie. where a person with capacity is:

- at risk of serious harm or death, and

- refuses all offers of support or interventions, or

- is unduly influenced by someone else.

The High Court has powers to intervene in such cases, although the presumption is always to protect the adult’s human rights.

Legal advice should be sought before taking this option.

Best interests decision making

If an adult is assessed as not having capacity to make decisions in relation to their self-neglect, any subsequent decisions or acts should be made in the adult’s best interests.

Any best interests decisions should be taken formally, and involve relevant professionals and anyone with an interest in the adult’s welfare, such as family. Additionally, consideration should be given as to whether an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) should be instructed.

Best interests must be determined by what the person would want were they to have capacity. “Lacking capacity is not an off switch for freedoms” (Wye Valley NHS Trust v Mr B, 2015, EWOCP 60). Therefore, in situations where an adult has experienced self-neglect over a long time and then loses capacity, previous behaviours must be considered when looking at the less restrictive options to keep the person as safe as possible.

If there are difficulties in making a best interests decision, it may be necessary to seek legal advice. In particularly challenging and complex cases, it may be necessary to make a referral to the Court of Protection for a best interests decision. Any referral to the Court of Protection should be discussed with Legal Services, including where there may be a ‘reasonable belief’ of lack of decision-specific capacity in situations where an adult is not engaging or refuses an assessment.

Multi-agency meetings

These procedures apply to all multi-agency meetings arranged in response to self-neglect whether they are taken into a safeguarding enquiry under Section 42 of the Care Act or managed outside of this.

Given the complex nature of self-neglect, responses by a range of organisations are likely to be more effective than a single agency response, and a co-ordinated approach is therefore essential. Multi-agency meetings are often the best way to ensure effective information sharing and communication, and a shared responsibility for assessing risks and agreeing an action plan.

A multi-agency planning meeting may be the best approach where:

- an adult has been identified as potentially self-neglecting,

- is refusing support, and

- by refusing support is placing themselves or others at risk of significant harm.

A multi-agency planning meeting, with a clear agenda for discussion, will be convened promptly when the initial concerns are raised. The purpose of this meeting is to offer an effective response, driven by the adult circumstances of the case.

Principles of a multi-agency planning meeting

- A lead agency will need to be identified (this will be the local authority where a safeguarding enquiry is being undertaken).

- The lead agency will be responsible for convening this meeting and making arrangements such as venue and minute taking.

- At the meeting, a decision will be made as how best to involve the adult. Best practice is to involve the adult as early on in the process as is practicable. The lead agency should provide support in making arrangements to enable the adult’s involvement.

- If the adult does not wish to or is unable to attend, it will be agreed how information will be fed back to them. Consideration should be given to ensuring the adult is provided with accessible information, and advocacy support should be offered if required.

- The meeting will be formally chaired, and responsibilities recorded on a shared action plan with named adults identified for each action.

- A fully co-ordinated response will be essential to achieving a satisfactory outcome, therefore there must be a clear understanding of the agreed way forward.

- Where there is disagreement this should be discussed until agreement is reached and if necessary line management consulted in order to resolve the situation.

- Participants need to come prepared with required information and ensure any actions have been carried out.

- Each agency approached will take responsibility for making any contacts or taking any actions considered necessary before the planning meeting.

Purpose of the multi-agency planning meeting

To review:

- The adult’s views and wishes as far as they are known.

- Information, actions and current risks.

- The ongoing lead professional or agency that will co-ordinate this work.

- The shared action plan and evaluate considered approaches.

- Assessments or discussions regarding the adult’s mental capacity up to that point.

Reason for convening a meeting

- Interventions have not reduced the level of risk, and a significant risk remains.

- It has not been possible to co-ordinate a multi-agency approach through work undertaken until this point.

- The level of risk requires formal information sharing and recording of the agreed multi-agency plan.

Timescales

Each adult’s situation is unique. Timescales for achieving actions should be set at the meeting and will be specified within the shared action plan. This will include timescales for completing any outstanding or more specialist assessments.

A date will also need to be set for a review meeting so that any further specialist assessments can be considered and any revised actions agreed.

Seeking legal advice

These procedures are not a substitute for agencies seeking legal advice where this is required.

Legal advice should be obtained and a legal representative could also be invited to the multi-agency planning meeting to hear the circumstances of the case and discuss relevant legal options that will:

- protect the person’s rights,

- meet the professional duty of care, and

- may lead to resolving the situation.

Outcome of the multi-agency meeting

- Update safeguarding or support plan and risk assessment.

- Identify actions – including contingency plans and escalation process.

- Agree monitoring and review arrangements.

- Identify other key adults information may need to be shared with.

- Agreement regarding the ongoing lead agency.

- Plans put in place regarding mental capacity assessments that may be required.

Minutes of multi-agency meetings

Minutes of multi-agency meetings will be sent to all attendees, as well as the adult concerned. The minutes will include:

- A written record setting out what support has been offered and / or is available, and why.

- The written record will include reasons if the adult refuses to accept any intervention.

- The written record will make it clear that, should the adult change their mind about their need for support, then contacting the relevant agency at any time in the future will trigger a re-assessment.

- Careful consideration will be given as to how this written record will be given, and where possible explained, to the adult.

Where the adult has previously not engaged in the process but then expresses a wish to be involved, a multi-agency meeting should be convened at the earliest opportunity and the shared action plan reviewed.

Following the multi-agency planning meeting, assessments should be brought together in one place so each professional involved will have an understanding of the links between their own involvement, and that of others. The impact the adult’s various care needs have on their functioning also needs to be understood and shared. The lead agency is responsible for collating this information into their agency assessment document, and sharing this with partner agencies.

Specialist input may be required to clarify certain aspects of the adult’s functioning and risk. This will be arranged, and the findings considered.

Key components of the comprehensive assessment of self-neglect neglect may include:

- A detailed social and medical history.

- Activities of daily living (eg. ability to use the phone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, mode of transport, responsibility for own medication, ability to handle finances).

- Environmental assessment.

- Cognitive assessment.

- A description of the self-neglect.

- A historical perspective of the situation.

- A physical examination – undertaken by a nurse or a medical practitioner.

- The adult’s own narrative on their situation and needs.

- The willingness of the adult to accept support.

- The views of family members, healthcare professionals and other people in the adult’s network.

- The adult’s understanding of the consequences of risks and neglect.

Note Record fully when and where the adult was assessed as having mental capacity to understand the consequences of their actions.

The risks of not intervening must be explored, and documented.

Outcomes determined following a multi-agency meeting and assessment of risk

Following the multi-agency meeting and comprehensive assessment, the risk to the adult should be evaluated. This should include:

- Risks identified and level of risk (low / medium / high). Likelihood and severity of risk to be considered.

- The adult’s wishes.

- How risks will be managed, including the adult’s protective factors.

- Ongoing monitoring arrangements and who is responsible for doing this.

- Contingency plan if risk increases, including if legal advisors should be involved or an escalation process.

The evaluation of risk should also include review arrangements and, where appropriate, making proactive contact with the adult to ensure that their needs, risks and rights are being considered.

If risk remains due to refusal by professionals or third parties to engage and this results in the neglect of the adult, consideration will be given to raising a safeguarding concern on the grounds of neglect. Raising a concern should be considered where professionals and third parties (with established responsibility for an adult’s care) either:

- do not engage with multi-agency planning, or

- seek to terminate their involvement prematurely (and this will pose a risk or harm to the adult).

If significant and ongoing risk remains, it may be necessary to convene a multi-agency review meeting. This review is an opportunity to revisit the original assessment and safeguarding or support plan, particularly in relation to:

- current functioning,

- risk assessment, and

- known or potential rates of improvement or deterioration in:

- the adult,

- their environment, or

- in the capabilities of their support system.

Decision-specific mental capacity assessments will have been reviewed and should be shared at the meeting. Discussion will need to focus upon contingency planning based upon risk.

It may be decided to continue providing opportunities for the adult to accept support and to monitor the situation. Clear timescales will be set for providing opportunities and for monitoring.

Where possible, indicators that risks may be increasing will be identified, and these indicators will trigger agreed responses from agencies, organisations or adult’s involved in a proactive and timely way.

There will be multi-agency agreement to the timescales set according to the circumstances of the case.

The chair of the multi-agency review will ensure clarity is brought to timescales for implementing contingency plans, to ensure that any legal and professional remedies are applied so risk is responded to and harm is prevented.

All relevant professionals will attend the multi-agency review so that:

- information is shared,

- contingency planning is fully discussed, and

- multi-agency ownership of the plans is achieved.

It is important to ensure an objective and fresh perspective is maintained as far as possible throughout this process. Consider the following approaches:

- Including people with relevant skills and experience who have not previously been involved.

- Ensure chronologies are up-to-date with multi-agency information, and analysed as part of the review of risk assessments and support plans.

- Whether escalation of some or all issues to more senior management may assist or provide any benefit (for example, consideration of an organisation’s internal risk panel).

A further meeting date will be set at each multi-agency review until there is agreement that the situation has become stable and the risk of harm has reduced to an agreed acceptable level.

Where agencies are unable to implement support or reduce risk significantly, the reasons for this will be fully recorded and maintained on the adult’s file, with a full record of the efforts and actions taken. There may come a point where all options have been exhausted and no further interventions can be planned. In these cases, mechanisms must be in place to monitor the ongoing risks with robust contingency plans to manage any escalation of risk.

The adult, carer or advocate will be fully informed of the support offered and the reasons why the support has not been implemented. The risks must be shared with the person to ensure they are fully aware of the consequences of their decisions, including the risk of death.

Respect for the wishes of the adult does not mean passive compliance – the consequences of continuing risk should always be explained and explored with the person.

The adult should be informed that they can contact the relevant agency at any time in the future for support.

A case will not be closed solely on the grounds of an adult refusing to accept the support plan and the above options should be thoroughly explored.

Refer to Appendix 1: Legal Remedies.

This checklist is not exhaustive; it is intended to be used as a guide throughout the process for the manager and / or practitioner to be able to reflect on the self-neglecting situation. The checklist can be used as a tool at the planning or closing stage or during supervision as an aide or prompt to help to consider some of the key stages of the intervention. Clicking on the links will access the relevant section of the procedures.

|

Has a person-centred approach been adopted? |

|

|

Has a decision-specific mental capacity assessment been indicated / completed? |

|

|

Have all the appropriate agencies / organisations been engaged in the process? |

|

|

Has the lead agency co-ordinated information gathering, and identified and implemented actions and outcomes? |

|

|

Has a Care Act 2014 assessment been considered? |

|

|

Has a safeguarding enquiry been considered? |

|

|

Has a multi-agency meeting been considered? |

|

|

Has a multi-agency risk assessment been completed? |

|

|

Has the adult, carer or advocate been kept informed throughout the process, and are those involved fully aware of the consequences of their decisions? |

|

|

Is legal advice required? e.g. if the adult is refusing to accept the support plan. |

|

|

Have accurate records been maintained that demonstrate adherence to the self-neglect procedures and locally agreed recording policies? |

|

|

Have ongoing multi-agency monitoring and reviewing arrangements been agreed? |